Cubic field

In mathematics, specifically the area of algebraic number theory, a cubic field is an algebraic number field of degree three.

Contents |

Definition

If K is a field extension of the rational numbers Q of degree [K:Q] = 3, then K is called a cubic field. Any such field is isomorphic to a field of the form

where f is an irreducible cubic polynomial with coefficients in Q. If f has three real roots, then K is called a totally real cubic field and it is an example of a totally real field. If, on the other hand, f has a non-real root, then K is called a complex cubic field.

A cubic field K is called a cyclic cubic field, if it contains all three roots of its generating polynomial f. Equivalently, if it is a Galois extension of Q, in which case its Galois group over Q is cyclic of order three. This can only happen if K is totally real. It is a rare occurrence in the sense that if the set of cubic fields is ordered by discriminant, then the proportion of cubic fields which are cyclic approaches zero as the bound on the discriminant approaches infinity.[1]

A cubic field is called a pure cubic field, if it can be obtained by adjoining the real cube root ![\sqrt[3]{n}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/46421f6b4261821f85f2a3c3bea53984.png) of a cubefree positive integer n to the rational number field Q. This can only occur if K is complex.

of a cubefree positive integer n to the rational number field Q. This can only occur if K is complex.

Examples

- Adjoining the real cube root of 2 to the rational numbers gives the cubic field Q(

![\scriptstyle\sqrt[3]{2}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/02ea788e2f58ff13dd3fcb9fa670e2a4.png) ). This is an example of a pure cubic field, and hence of a complex cubic field. In fact, of all pure cubic fields, it has the smallest discriminant (in absolute value), namely −108.[2]

). This is an example of a pure cubic field, and hence of a complex cubic field. In fact, of all pure cubic fields, it has the smallest discriminant (in absolute value), namely −108.[2]

- The complex cubic field obtained by adjoining to Q a root of x3 + x2 − 1 is not pure. It has the smallest discriminant (in absolute value) of all cubic fields, namely −23.[3]

- Adjoining a root of x3 + x2 − 2x − 1 to Q yields a cyclic cubic field, and hence a totally real cubic field. It has the smallest discriminant of all totally real cubic fields, namely 49.[4]

- The field obtained by adjoining to Q a root of x3 + x2 − 3x − 1 is an example of a totally real cubic field that is not cyclic. Its discriminant is 148, the smallest discriminant of a non-cyclic totally real cubic field.[5]

- No cyclotomic fields are cubic because the degree of a cyclotomic field is equal to φ(n), where φ is Euler's totient function, which only takes on even values (except for φ(1) = φ(2) = 1).

Galois closure

A cyclic cubic field K is its own Galois closure with Galois group Gal(K/Q) isomorphic to the cyclic group of order three. However, any other cubic field K is a non-galois extension of Q and has a field extension N of degree two as its Galois closure. The Galois group Gal(N/Q) is isomorphic to the symmetric group S3 on three letters.

Associated quadratic field

The discriminant of a cubic field K can be written uniquely as df 2 where d is a fundamental discriminant. Then, K is cyclic if, and only if, d = 1, in which case the only subfield of K is Q itself. If d ≠ 1, then the Galois closure N of K contains a unique quadratic field k whose discriminant is d (in the case d = 1, the subfield Q is sometimes considered as the "degenerate" quadratic field of discriminant 1). The conductor of N over k is f, and f 2 is the relative discriminant of N over k. The discriminant of N is d3f 4.[6][7]

The field K is a pure cubic field if, and only if, d = −3. This is the case for which the quadratic field contained in the Galois closure of K is the cyclotomic field of cube roots of unity.[7]

Discriminant

Since the sign of the discriminant of a number field K is (−1)r2, where r2 is the number of conjugate pairs of complex embeddings of K into C, the discriminant of a cubic field will be positive precisely when the field is totally real, and negative if it is a complex cubic field.

Given some real number N > 0 there are only finitely many cubic fields K whose discriminant DK satisfies |DK| ≤ N.[9] Formulae are known which calculate the prime decomposition of DK, and so it can be explicitly calculated.[10]

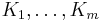

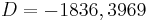

However, it should be pointed out that, different from quadratic fields, several non-isomorphic cubic fields  may share the same discriminant D. The number m of these fields is called the multiplicity[11] of the discriminant D. Some small examples are

may share the same discriminant D. The number m of these fields is called the multiplicity[11] of the discriminant D. Some small examples are  for

for  ,

,  for

for  ,

,  for

for  , and

, and  for

for

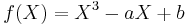

Any cubic field K will be of the form K = Q(θ) for some number θ that is a root of the irreducible polynomial

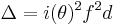

with a and b both being integers. The discriminant of f is Δ = 4a3 − 27b2. Denoting the discriminant of K by D, the index i(θ) of θ is then defined by Δ = i(θ)2D.

In the case of a non-cyclic cubic field K this index formula can be combined with the conductor formula  to obtain a decomposition of the polynomial discriminant

to obtain a decomposition of the polynomial discriminant  into the square of the product

into the square of the product  and the discriminant d of the quadratic field k associated with the cubic field K, where d is squarefree up to a possible factor

and the discriminant d of the quadratic field k associated with the cubic field K, where d is squarefree up to a possible factor  or

or  . Georgy Voronoy gave a method for separating

. Georgy Voronoy gave a method for separating  and f in the square part of

and f in the square part of  .[12]

.[12]

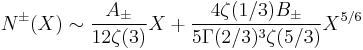

The study of the number of cubic fields whose discriminant is less than a given bound is a current area of research. Let N+(X) (respectively N−(X)) denote the number of totally real (respectively complex) cubic fields whose discriminant is bounded by X in absolute value. In the early 1970s, Harold Davenport and Hans Heilbronn determined the first term of the asymptotic behaviour of N±(X) (i.e. as X goes to infinity).[13][14] By means of an analysis of the residue of the Shintani zeta function, combined with a study of the tables of cubic fields compiled by Karim Belabas (Belabas 1997) and some heuristics, David P. Roberts conjectured a more precise asymptotic formula:[15]

where A± = 1 or 3, B± = 1 or  , according to the totally real or complex case, ζ(s) is the Riemann zeta function, and Γ(s) is the Gamma function. A proof of this formula has been announced by Bhargava, Shankar & Tsimerman (2010).

, according to the totally real or complex case, ζ(s) is the Riemann zeta function, and Γ(s) is the Gamma function. A proof of this formula has been announced by Bhargava, Shankar & Tsimerman (2010).

Unit group

According to Dirichlet, the torsionfree unit rank r of an algebraic number field K with  real embeddings and

real embeddings and  pairs of conjugate complex embeddings is determined by the formula

pairs of conjugate complex embeddings is determined by the formula  . Hence a totally real cubic field K with

. Hence a totally real cubic field K with  has two independent units

has two independent units  and a complex cubic field K with

and a complex cubic field K with  has a single fundamental unit

has a single fundamental unit  . These fundamental systems of units can be calculated by means of generalized continued fraction algorithms by Voronoi,[16] which have been interpreted geometrically by Delone and Faddeev.[17]

. These fundamental systems of units can be calculated by means of generalized continued fraction algorithms by Voronoi,[16] which have been interpreted geometrically by Delone and Faddeev.[17]

Notes

- ^ Harvey Cohn computed an asymptotic for the number of cyclic cubic fields (Cohn 1954), while Harold Davenport and Hans Heilbronn computed the asymptotic for all cubic fields (Davenport & Heilbronn 1971).

- ^ Cohen 1993, §B.3 contains a table of complex cubic fields

- ^ Cohen 1993, §B.3

- ^ Cohen 1993, §B.4 contains a table of totally real cubic fields and indicates which are cyclic

- ^ Cohen 1993, §B.4

- ^ Hasse 1930

- ^ a b Cohen 1993, §6.4.5

- ^ a b The exact counts were computed by Michel Olivier and are available at [1]. The first-order asymptotic is due to Harold Davenport and Hans Heilbronn (Davenport & Heilbronn 1971). The second-order term was conjectured by David P. Roberts (Roberts 2001) and a proof has been announced by Manjul Bhargava, Arul Shankar, and Jacob Tsimerman (Bhargava, Shankar & Tsimerman 2010).

- ^ H. Minkowski, Diophantische Approximationen, chapter 4, §5.

- ^ Llorente, P.; Nart, E. (1983). "Effective determination of the decomposition of the rational primes in a cubic field". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 87 (4): 579–585. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1983-0687621-6.

- ^ Mayer, D. C. (1992). "Multiplicities of dihedral discriminants". Math. Comp. 58 (198): 831–847 and S55–S58. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1992-1122071-3.

- ^ G. F. Voronoi, Concerning algebraic integers derivable from a root of an equation of the third degree, Master's Thesis, St. Petersburg, 1894 (Russian).

- ^ Davenport & Heilbronn 1971

- ^ Their work can also be interpreted as a computation of the average size of the 3-torsion part of the class group of a quadratic field, and thus constitutes one of the few proven cases of the Cohen–Lenstra conjectures.

- ^ Roberts 2001, Conjecture 3.1

- ^ Voronoi, G. F. (1896) (in Russian). On a generalization of the algorithm of continued fractions. Warsaw: Doctoral Dissertation.

- ^ Delone, B. N.; Faddeev, D. K. (1964). The theory of irrationalities of the third degree. Translations of Mathematical Monographs. 10. Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society.

References

- Şaban Alaca, Kenneth S. Williams, Introductory algebraic number theory, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Belabas, Karim (1997), "A fast algorithm to compute cubic fields", Mathematics of Computation 66 (219): 1213–1237, MR1415795

- Bhargava, Manjul; Shankar, Arul; Tsimerman, Jacob (2010). "On the Davenport–Heilbronn theorem and second order terms". arXiv:1005.0672.

- Cohen, Henri (1993), A Course in Computational Algebraic Number Theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 138, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-55640-4, MR1228206

- Cohn, Harvey (1954), "The density of abelian cubic fields", Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 5: 476–477, MR0064076

- Davenport, Harold; Heilbronn, Hans (1971), "On the density of discriminants of cubic fields. II", Proceedings of the Royal Society. London. Series A 322 (1551): 405–420, MR0491593

- Hasse, Helmut (1930), "Arithmetische Theorie der kubischen Zahlkörper auf klassenkörpertheoretischer Grundlage" (in German), Mathematische Zeitschrift 31 (1): 565–582, doi:10.1007/BF01246435

- Roberts, David P. (2001), "Density of cubic field discriminants", Mathematics of Computation 70 (236): 1699–1705, MR1836927

![\mathbf{Q}[x]/(f(x))](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8b2481b53e94dea41da4482df12fbaca.png)